——————————————————————–

John Lennon: Essence and Reality Part 11: “Imagine”

Lennon was pragmatic enough to know that, at some point, people who

seek freedom will need to act. He was sufficiently experienced to know

that music can inspire people to act. And he was wise enough to know

that the first act to liberation is one of the imagination. Freedom is,

first of all, a liberation of consciousness. But freedom for what? All

these issues, and more, Lennon addressed in three minutes and six

seconds in his tour de force, “Imagine”.

“Imagine” is, without doubt, Lennon’s signature song, his anthem: a

call to an idyllic world of benevolence and peace. But every force

evokes an opposite reaction, and so does every torch song. “Imagine” is

also his most widely detested song because of its opening line “Imagine

there’s no heaven”, which effectively, of course, means no Christian

god, for as the Lord’s Prayer says, our father is in heaven.

Lennon himself remarked that the song was anti-religion and

anti-capitalist, but that it was ‘accepted’ because it was

‘sugar-coated’. And this is largely, although not entirely, true. Many

people who cherish it as an anthem do not really think about what the

song says, although they understand what it’s about. While the lyrics

could hardly be any clearer, the “unspoken lyrics” of the music, to put

it that way, are yet clearer and louder. I am not taking a position for

or against the song, but an exploration would repay the effort, because

there is something very big, even massive, in “Imagine”. I think that

people are attracted to this, the big spirit that breathes through the

song as a whole.

First of all, some context. The Beatles had split up only about a

year before Lennon started working on this song and the album of the

same name. His reputation had suffered: for example, he was variously

decried as a ratbag, a hypocrite, a fool, and even naive. Oddly, it

seems that the accusation of naivety was the one which hurt him the

most. People can disagree on morality, or even on what constitutes

wisdom or its opposite, but to call someone naive is to deny them adult

status, to refuse to take them seriously. I think that we all doubt

ourselves, to some extent and in some areas, and so to be mocked out of

a fair hearing is painful because it confirms our secret fears, based

as they are upon our own criticism of ourselves.

It’s as if we all have a custom made wound between our shoulder

blades, and the knife which fits the wound is “ridicule”. Lennon would

pretend not to be bothered by it, but he was, and so, thankfully, he

stopped performing “bed-ins”, appearing in a bag in the name of “total

communication”, or growing his hair for peace. Lennon adopted all the

trendy left-wing political postures, and hob-nobbed with the “yippie”

Abbie Hoffman and his ilk. Yet, even during this period he produced

what is, to my ear, the rock and roll album without parallel, John

Lennon /Plastic Ono Band. Despite the excess of one track (“Well, Well,

Well”), it is still easily the deepest single piece of music produced

in the last 50 years, at least so far as my knowledge extends and my

taste discerns (see my blogs on “God” and “Remember”).

But that record had not met with the popular success Lennon believed

it deserved, and for which he craved. So he did what he later would

when his Some Time In New York City double album was a spectacular

flop: he changed tack to something he fancied would be more in tune

with the market. After Some Time, he produced Mind Games, which was

received with relief, although not the sales he had hoped for. After

John Lennon he produced Imagine, and that was a success. The only track

on it that most people find hard to listen to today is “I Don’t Wanna

Be A Soldier”, a wailing, indulgent anti-war piece, which thankfully

ends side 1, so that in the days of vinyl one could simply lift the

needle off early.

Now, I am not saying that the song “Imagine” was insincere, or that

it was contrived to meet the market. It in fact has roots deep in

Lennon’s artistry, and is his authentic voice. But I think that the

song was produced so as to maximize its popular success. One could

compare it to “Love” from the John Lennon album. There, the melody is

almost achingly beautiful, something Lennon was proudly aware of, and

it was given a beautiful production which was simplicity itself, care

of none other but Phil Spector, who was celebrated for his large

productions. However, it was the sort of treatment which only the

cognoscenti would really appreciate: for that type of song, the record

buying public tends to prefer strings. And so “Imagine” had strings.

But it had more: its very first line, considered apart from its soft

musical treatment, was either startling or confronting, depending on

your point of view:

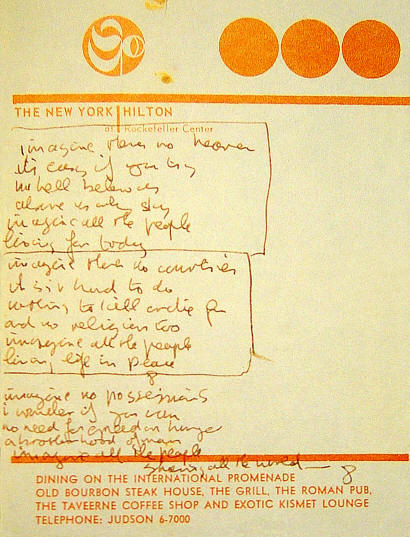

Imagine there’s no heaven, it’s easy if you try;

No hell below us, above us only sky.

Imagine all the people living for today – ah ah, aye.

At the Catholic school I attended at the time of this song’s

release, Brother Terence, our class teacher, played us “Imagine” and

“Gimme Some Truth” as contemporary songs we could profitably ponder. He

was not threatened by any of its concepts, and what is more, he entered

into the spirit of the lyrics. The thing was, he said, to actually

imagine it. To stop, get other things out of your mind for three

minutes, and try to see it. And that really is the song in a nutshell.

But let’s go back.

First of all, the piano lead in is stately, even hymnic. It was

intended to, and it does have an anthemic quality. On another version,

released only posthumously on the four volume Anthology, this aspect is

even more strikingly emphasised, because the chief accompanying

instrument there is an organ, on which decidedly churchy stops have

been pulled. Given the anti-religious sentiments of the lyrics, this is

almost ironic. But there is a point to this, because it means that the

song aspires to ideals usually associated exclusively with religion.

This, I am sure, is true to the paradox of Lennon. In 1980 he told an

interviewer (David Shef) that he was a religious person, and went on to

say that he had no problems with what Jesus had taught, but that people

were mesmerised by Jesus, not his message. Indeed, during that

interview Lennon made frequent reference to Jesus, and his miracles

such as the loaves and fishes! Lennon was marked by ambiguity and

love/hate. In the early 1970s, Lennon was still in two minds as to

whether the real issues were political and social, or psychological and

perhaps even spiritual. After Mind Games, he would retreat from overtly

political statements and concerns, and turn more innerly.

It seems to me that most criticisms of Christianity and Christians,

and Lennon’s is no exception, are in fact taking aim at a lack of

Christianity, at a failure to live like Christians. With relatively few

exceptions, it is not Christianity that people object to but the lack

of Christianity, and this is of course harder to accept when there is

hypocrisy in the equation. What Lennon is getting at in “Imagine” goes

beyond this: he is not attacking Christianity by name, but rather

religion and concepts such as God and hell, anything which takes one

away from “living for today”, as he puts it. The song goes on to then

erase other fixtures of our mental furniture:

Imagine there’s no countries, it isn’t hard to do,

Nothing to kill or die for, and no religion, too.

Imagine all the people living life in peace.

You may say I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one.

I hope some day you’ll join us, and the world will be as one.

Imagine no possessions, I wonder if you can.

No need for greed or hunger, a brotherhood of man.

Imagine all the people sharing all the world.

You may say I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one.

I hope some day you’ll join us, and the world will live as one.

On a live performance, he would sing in the final verse “a

brotherhood and sisterhood of man”. He did not correct his sexism by

altering “man” to “people” or something less redolent of machismo.

But all that side of things is a distraction: what is critical about

this song is an insight which he took from Yoko Ono, and that is this:

envisaging a possibility and imagining its reality are the first steps

to making it a reality. This can be a trite statement, but it can also

be profound, even revelatory. So many of our limitations are accepted

by us simply because we cannot imagine an alternative. It is

astounding, even horrifying, in a way, to wake up and realise that we

are limited in our reactions and our responses simply because we have

never seen anyone react in any other way. That is, we see that “X”

always “makes” people get upset, and something in us, something which

is so deep as to rarely be in our awareness, has a sense that there

would be something wrong if we, too, did not upset when “X” happened. I

shall develop this idea further in a future blog, when I deal with

“How?”, also from the Imagine album. In “The Daphne Blossom”, also

available on this blog by kind permission of Carl Ginsberg, one can

read how Ginsberg, a Feldenkreis practitioner, cured a problem George

Adie had with swallowing food, by inducing him to imagine the existence

of the lung which had been surgically removed almost 40 years earlier:

and what is more, it worked, almost like magic.

And perhaps imagination and magic are related. This, I think, makes

sense of much of Yoko Ono’s art, although, as I have said before, I do

not pretend to understand that redoubtable woman and her approach.

Imagination, in the sense of consciously forming an image and

introducing it into one’s thought and feeling as an active element, was

a stable of her art, as even a cursory glance at her book Grapefruit

will show. What Lennon and One were saying is that we receive all sorts

of influences through the media and society. Most of these, as the

correctly saw, were based on unthinking prejudices and attitudes. Most

of these are were needlessly crass and low, hence on “Working Class

Hero” from John Lennon/ Plastic Ono Band, he sings: “you’re still

fucking peasants as far as I can see”. But, and this is why Lennon and

Ono were so excited, one has a choice: one can choose to look for

better influences, and what is more, everyone can create such

influences by using their minds creatively.

We are forever manufacturing our own present and future through our

imaginations. This, I think, is the essence of what Yoko Ono brought

Lennon, and it was a lesson for which he had long ago prepared the

ground: see my blog on “There’s A Place”. Any comment on Lennon’s

relationship with Ono which does not take this into account, is, in my

view, hopelessly superficial.

To return to the metaphor of the magician, the wizard and the witch

(as Yoko referred to John and herself on “You’re The One” from Milk and

Honey) have to visualize what they desire, but then they have to have

sufficient knowledge. Some things can be effected merely by thought:

methods of self-suggestion work on this basis. But other things cannot

be so easily dealt with: and there is the issue. People who have

learned of the power of the mind tend to become overly enthusiastic and

imagine that there are no limits to it. This is absurd as imagining

that nothing can be effected by creative visualisation. Lennon had some

insight into this: he saw that it is not just a case of thinking about

something like peace. Lennon realised that it needs to be pictured as a

reality, and pictured clearly and distinctly desired. That is why he

sang: “some day you’ll join us, and the world will be as one.” What

cannot be done by parliaments, or United Nations can be done by people:

as he sang on “Only People” from Mind Games: “only people know just how

to change the world.”

And for what is this freedom desired? So that the world may live as

one, sharing the world, in peace. It would be easy to critique this as

naive or as amorphous, and to show that belief in heaven, hell and

religion are not the problem, but rather, as I have said, lip-service

and hypocrisy, that is, insufficient practice of religion. As for the

idea that eliminating possessions would also spell the end of greed and

hunger – well this is naivety of an almost criminal level. What could

Lennon had been thinking? Was he merely reciting hoary old Socialist

opium dreams?

But I do not particularly want to take a shot at “Imagine” today.

The deficiencies in the lyrics are somewhat made up in the music, and

the nobility of what he was aiming at: the transformation of negative

emotions into positive, what Gurdjieff called the second conscious

shock (see In Search of the Miraculous, p.191). I have no evidence that

is even suggestive that Lennon was acquainted with Gurdjieff’s ideas,

and yet, that is what I hear in “Imagine”: the conviction that hatred

can be transformed through consciousness, and that divisions can be

overcome by a positive impulse. All that is lacking is an understanding

of the necessity of the first conscious shock: that is, that we cannot

bring a conscious influence to our emotions unless we first of all

remember ourselves. But Lennon had started to move towards this

insight, realizing that for years he had forgotten himself (see the

first Lennon blog). And I think that some form of this insight may lie

behind the reference to people “living for today”. Is it too hopeful of

me to see Lennon saying that we need to be present?

There is far more one could say, but I shall return to what I see as

the crucial points in future blogs, where I shall take other songs as

my point of departure. But I shall end this one by pointing out

elements of continuity and development in Lennon’s artistic career. As

has been noticed before, the first words of “Imagine” were foretold, as

it were, in “I’ll Get You” from 1963, where Lennon sang: “Imagine I’m

in love with you, it’s easy ‘cos I know, I’ve imagined I’m in love with

you, many, many, many times before.” (e.g. S. Turner, The Beatles: The

Stories behind the Songs 1962-1966). However, what Turner does not

note, is that in 1963 Lennon went on to sing: “It’s not like me to

pretend …”. In 1971, not so long afterwards, Lennon saw that

imagination was a tool in the technology of consciousness.

He had indeed, come a long way. But he had further to go, and in the

next blog, I’ll consider one of his final songs, where he showed that,

without any doubt, his feet were finding their place on the earth while

he had lost nothing of his idealism: “Clean Up Time” from Double

Fantasy.

Joseph.Azize@googlemail.com

———————————————

Joseph Azize has published in ancient history,

law and Gurdjieff studies. His first book The Phoenician Solar Theology

treated ancient Phoenician religion as possessing a spiritual depth

comparative with Neoplatonism, to which it contributed through

Iamblichos. The second book, “Gilgamesh and the World of Assyria”, was

jointly edited with Noel Weeks. It includes his article arguing that

the Carthaginians did not practice child sacrifice.

The third book, George Mountford Adie: A

Gurdjieff Pupil in Australia represents his attempt to present his

teacher (a direct pupil of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky) to an international

audience.The fourth book, edited and written with

Peter El Khouri and Ed Finnane, is a new edition of Britts Civil

Precedents. He recommends it to anyone planning to bring proceedings in

an Australian court of law.

| Группа "Гости" | RSS

| Группа "Гости" | RSS

| Группа "Гости" | RSS

| Группа "Гости" | RSS