——————————————————————–

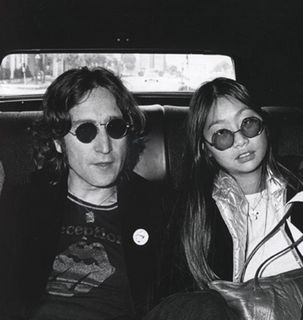

John Lennon & May Pang

“# 9 DREAM”.

I once had a dream where I was sweeping the cloistered walk of a

temple courtyard. It strangely resembled one I had seen in Turkey:

ostensibly a school of traditional music, I had suspected that this

Turkish school was in fact connected with Sufism. In my dream, as in

life, a strong sense of peace of security possessed the scene. Across

one of the cloisters there were hung brightly woven curtains. I was

quite light-hearted, and was almost finished sweeping, when someone

asked me if I would like to have my fortune told. Across the courtyard

garden, others were having their palms read by women who were barely

more than teenagers. It all seemed a bit of a hoot, so, in a spirit of

fun, I said yes, I would have my fortune told. Directly, someone said

that the fortune-teller had arrived, and I felt a slight tremor. When I

saw her, something inside me drew back. She was a tall and noble

African, with high cheek-bones, a multi-coloured turban, and something

of that impersonal, hierarchical presence which Nina Simone commanded.

She seemed to displace the air rather than to walk, and she was

accompanied by two men, one a bearded man in middle age, and the other

an unshaven and demented youth. Somehow, I knew that they meant

business. This was the real thing. I was in two minds about going ahead

with the consultation, but I found my courage. I sat cross-legged,

opposite her, while the two men looked on. She took my left hand with

her right, and drew my arm forward. Then she laid the fingers of her

left hand on the flesh of my left forearm, placing a slight pressure on

the veins. Immediately, sensation filled my body and flowed over into

an electric sensation, which took me into another state.

I know how far short these words fall of communicating the

experience, and its present significance for me. Yet, the dream is a

source of confidence. Perhaps the most I can do is suggest something

which you can then relate to a similar dream you may have had. However,

some poets and musicians have had more success in communicating these

sendings. Samuel Taylor Coleridge managed to evoke an eerie power in

“Kubla Khan”, his account of an opium dream. Interestingly, he was

moved by the music he heard played and sang by “an Abyssinian maid”

with a dulcimer. However, the music had passed from him, as it were,

causing him to say that “If I could revive within me her symphony and

song”, it would make him a man of altogether different capacities and

powers.

I feel that in “#9 Dream”, John Lennon fulfilled something of

Coleridge’s yen, and has fashioned a fantasy-ruby, an auditory vision

of roughly four and a half minutes’ duration. The first time I heard

this song, even though it was on a battered old radio with knobs and

switches falling off it, I was entranced and physically affected, I

could hardly stand. As is the way of things, no subsequent listening

has ever had the same effect, but maybe now the experience goes deeper,

to a place which is not so easily overcome by shock. Certainly, the

song has benignly haunted me for 35 years. Frequently I sing to myself

the opening words: “So long ago: was it in a dream? Was it just a

dream?” Even now, it conjures in me a different focus, as it were. It

reverberates with echoes of a far-away time, a far-away place, of

people and spirits separated only by a veil dancing just beyond my

finger tips. The tempo of the song is neither slow nor “dreamy”, and is

all the truer to dreams for taking a pleasant walking pace. The nice

tread of the music contributes to the sense of visionary reality –

there is nothing hallucinatory about this song, unlike “Lucy In The Sky

With Diamonds”. Yet, the melody line takes its time; the words are not

hurried. Some of the key words are subtly sustained, or given a light

stress. It sounds as if Lennon is singing the following:

So-oh long ago: was it in a dream? Was it just a dream?

I-hi know-oh, yes, I know, seemed so very real

Seemed so (un)real to me –

Took a walk down the street,

Through the heat whispered trees.

I thought I could hear, hear, hear, hear

Somebody called my name – “John, John”,

As it started to rain – “John”,

Two spirits dancing so strange,

Ah! bawawaka, po-say, po-say.

Ah! bawawaka, po-say, po-say.

Ah! bawawaka, po-say, po-say.

Dream, dream away – magic in the air, was magic in the air?

I believe, yes I believe,

More I cannot say, what more can I say?

On a river of sound,

Through the mirror go round (round),

I thought I could feel, feel, feel, feel

Music touching my soul, (whispering)

Something warm sudden cold,

The spirit dance was un-fold-ing,

Ah! bawawaka, po-say, po-say.

Ah! bawawaka, po-say, po-say.

Ah! bawawaka, po-say, po-say.

Ah! bawawaka, po-say, po-say (continued)

May Pang, Lennon’s then girlfriend, whispers his name and some other

words I cannot quite make out after the words “music touching my soul”.

There is nothing dramatic about Lennon’s delivery or the music, they

are almost understated, and yet they leave an impression. “So long ago:

was it in a dream? Was it just a dream?” I cannot imagine these words

being sung to any other tune, or the tune having more appropriate

words. In fact, all the words come out as naturally as if he were

speaking them with the unpractised emphasis of everyday conversation.

It seemed so very real, Lennon sings, and then he seems to say that

it “seemed so unreal to me”. Perhaps he was only taking an audible

breath before saying “real”. But it has always sounded to me as if he

were saying “real” and then “unreal”. He both said and unsaid himself

in an unreleased version of the Beatles’ song “Revolution”. which was

faithfully shown in the movie Imagine, so it is not impossible. The

song seems to imply that reality and unreality are two sides of one

coin in this dream existence. Indeed, the difference between them is

only a question of realisation. Once it has been dreamed, once it has

been imagined, the concept or feeling can be realised, even if the

realisation is itself an act of imaginative recreation.

I recall that Lennon was interviewed by a Sydney radio station when

the album Walls and Bridges was released in 1974. He said that in the

song he had described the dream exactly as it happened: so he will have

seen himself walking down a familiar street, in hot weather, as trees

whispered to him, and someone called his name. The DJ asked him about

the spirit mantra “Ah! bawawaka, po-say, po-say”. Lennon answered with

disarming simplicity that this was what it sounded to him the spirits

were saying.

Was magic in the air? he asks. And he replies, yes, he believes it

was. As I have indicated, dreams can comfort, they can console, teach

and inspire belief. Thus it was for Lennon: as Lennon fans scholars

well know, “nine” was for Lennon the number of destiny, it was his

number. For many years he had taken drugs to break free from “the

straitjacket of the self”, as he said. Now, through a dream, he was

able to go through a mirror and around: through the image, coming back

to reality having seen the other side of his perception.

Finally he asks, what more could he say? And what can he say about

this mystery? What can be said by anyone about any mystery? Yet, he has

described something almost beyond description. Could you imagine a song

with the lyrics “I went through the image and came back to reality

having seen the other side of my perception”? This is what he has done

with the simple words “through the mirror go round”.

It seems to me that Lennon did receive an intimation of something high,

I might say “sacred”, in this dream. First, however, we must say a few

words about dreaming.

Dreams are the work, in Gurdjieff’s terms, of the “moving centre”

(”moving brain”). This centre, which is in charge of our learned

movements such as walking, talking, playing guitar, cleaning dishes and

so on, continues with a certain consciousness while we are asleep.

Generally, and especially during deep sleep, it is not connected with

the intellectual or emotional brains, and so the next morning we do not

recall the dreams. But if we are not fully asleep, then a faint

connection between the centres may subsist, and the intellect can

recall something of a dream the next morning. The moving centre, unlike

the intellectual centre, is not logical, it does not have a sense of

non-contradiction. Therefore, Gurdjieff said, it allows illogicalities

and impossibilities, the dreamer can speak with people who are dead. To

the extent that the moving and intellectual brains are disconnected

during dreams, dreams can be illogical. Gurdjieff told this to Mme

Lannes, and she passed the information on to Mr Adie, which is why I

can confidently attribute it to Gurdjieff.

I extrapolate from this that to the extent that the moving and the

feeling brains are unconnected, our dreams can have emotional aspects –

even fearsomely emotional aspects – but the moving centre does not know

this, so it blithely goes on creating dungeons and other tortures for

us. Meanwhile, the emotional centre is being racked by torments, but is

unable to convey this to the moving centre. It may, however, succeed in

getting its message to the instinctive centre (which controls the work

of the organism one does not have to consciously learn, such as

breathing, the circulation of the blood, digestion and so on). And when

the message gets through, we awaken. What Gurdjieff does not tell us is

why the moving brain dreams, and whether all dreams necessarily come

from moving brain.

George Adie’s view, with which I agree, is that the moving centre

dreams as a form of digestion. Impressions are received during the

waking day, and these impressions are not necessarily fully understood

or grasped by the other centres (see the diary note of 4 February 1987

in George Mountford Adie: A Gurdjieff Pupil in Australia, 283). Some

impressions are fairly unimportant, and leave little trace. So little

trace do they leave that they appear in dreams only as background. But

the concerns of our moving centre, and hence our dreams, tend to be

things which are of substantial importance to us. Generally, I find,

they relate to two fields: (a) matters where our ideas and feelings are

as yet unresolved, and (b) the transfer of patterns from intellectual

centre to moving centre. First, unresolved matters. If I have a bad

conscience about something (using that phrase in its ordinary sense),

if something has disturbed me, or, on the other hand, if something

caused me pleasure or an intense hope, it may reappear in dreams. It is

as though the moving centre has to file everything away into the

tidiest possible place. We are made for order. Significant matters need

extra filing, as it were. They demand extra attention, and if they are

not given satisfactory attention during the day from the intellectual

centre, then they demand it, so to speak, in sleep. So the connection

between the moving and intellectual centres is re-established, albeit

weakly, the prominent event is gone over with the help of the

intellect, and it is given new associations in the psyche – it is

acclimatized, as it were.

The filing carried out by the moving brain is not at all conducted

in the way the intellectual or the emotional centre would carry it out.

It seems to be performed according to a method of random associations

or, if not entirely random, of associations possessing a similar

intensity, and not necessarily of similar concepts. The result of this

is that strong impressions often produce strong dreams where one cannot

say what the dream message is, except that the impression was

considered important.

The second major function of the moving centre in sleep seems to me

to be to allow it to acquire skills learned by the intellectual centre

during the day. As Gurdjieff correctly pointed out, I learn typing with

the intellect, I have to. But eventually the moving brain takes it

over, and does a better job: it does not have to think about every

little thing. Well, I suspect that sleep is when the moving centre has

a clear field, in which it can learn these things without being crowded

out by the head. This would explain why the better we sleep the better

we learn.

All this suggests two things to me: one is that we are made to

understand. I can hardly insist on this enough, because at the moment

there is, in some circles, a sort of exaggerated enthusiasm for

non-understanding. It is true that some things cannot be understood,

but that hardly means that we should not try to understand them. The

very attempt may bring more understanding, or a grasp of other matters.

Indeed, I suspect that the allure of the mysterious is a providential

arrangement to arouse our curiosity, to evoke a pure love of knowledge

and discovery. To anaesthetize that impulse, so readily observed in

children is, it seems to me, criminal. I repeat, the fact that our

organism knocks out our intellect in order to use dreaming to arrange

and organize the day’s events seems to me to be evidence that we are

designed to seek understanding and the harmonisation of our various

impressions.

Also, and I add this to the blog because the idea may prove useful

for some people, I have found that by carrying out the exercise of

reviewing the day, I have fewer dreams, and those I do have tend to be

less intense. I refer here to the Gurdjieff exercise whereby one casts

one’s mind eye over the events of the day, and pauses when one comes to

anything important or worrying. It is not necessary to think about

these things, let alone to conduct an amateur psycho-analysis. In fact,

that may cause new problems. All that is necessary is to put oneself

before the memories, and then, I often find, a clearer understanding

starts to appear.

To understand “#9 Dream”, and something of the process of art

(higher art), I also think that some dreams come from other centres

than the moving brain: they can be the products of higher emotional

centre, and therefore speak in a natural symbolism – and this is

emphatically not the symbolism of dream dictionaries. The higher

emotional and higher intellectual centres are the two faculties,

existing in every person, which are the means of receiving and

transmitting influences from beyond this sensory world. When contact is

made between the intellect, and the higher emotional centre, said

Gurdjieff: “man experiences new emotions, new impressions hitherto

entirely unknown to him, for the description of which he has neither

words nor expressions.” However, because we are so rarely in such a

state of connection, ” we fail to hear within us the voices which are

speaking and calling to us from the higher emotional centre.” (P.D.

Ouspensky, In Search of the Miraculous, 194-195).

My view is that Lennon heard these voices of the higher emotional

centre calling him in a dream, and hence we have this marvellous song.

As May Pang said, when Lennon woke up the morning after the dream, he

had the words and the music together. If there has been a gift from the

gods in modern music, this, I would say, is it. So the mystery of

dreams is, or at least can be, related to the mystery of the life of

the soul, the spiritual life. And Lennon made the connection.

As I said in the last blog, Lennon invites us into mystery. He does not

make the mistake of trying to strip away the wonder by saying too much.

He displays the magic, as it were, by presenting it, highlighted, in

his own river of sound (and it should be added that Phil Spector was

probably the perfect producer to work with Lennon on this piece). “#9

Dream” marks the high water mark of a tide which had begun with

“There’s A Place”, on the Please Please Me album. Between these two

points, there is a reasonably substantial body of work which forms a

connecting trail. I cannot cover all of it, but in the next Lennon

blog, I shall deal with one central concept: the use of creative

imagination. I am referring, obviously, to what is Lennon’s signature

tune, the classic “Imagine”.

Joseph.Azize@googlemail.com

———————————————

Joseph Azize has published in ancient history, law and

Gurdjieff studies. His first book The Phoenician Solar Theology treated

ancient Phoenician religion as possessing a spiritual depth comparative

with Neoplatonism, to which it contributed through Iamblichos. The

second book, “Gilgamesh and the World of Assyria”, was jointly edited

with Noel Weeks. It includes his article arguing that the Carthaginians

did not practice child sacrifice.

The third book, George Mountford Adie: A Gurdjieff Pupil

in Australia represents his attempt to present his teacher (a direct

pupil of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky) to an international audience.The

fourth book, edited and written with Peter El Khouri

and Ed Finnane, is a new edition of Britts Civil Precedents. He

recommends it to anyone planning to bring proceedings in an Australian

court of law.

| Группа "Гости" | RSS

| Группа "Гости" | RSS

| Группа "Гости" | RSS

| Группа "Гости" | RSS