The spark of genius.

It was 1967, and the Beatles were at work on a sonic masterpiece with a 20-year-old recording engineer at their side.

By Christopher Ave

Published May 20, 2007

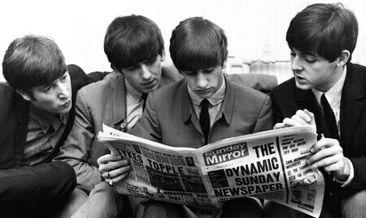

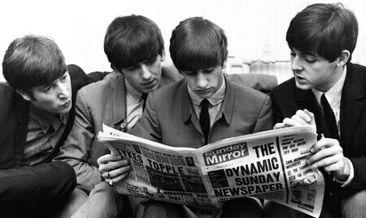

The Beatles at the launch of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,

London, 1967. Left to right, Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, John Lennon

and George Harrison. Special Report: A Splendid Time is Guaranteed for All

Illustration by Don Morris

Special Report: A Splendid Time is Guaranteed for All

Behind

the scenes: Listen to an audio interview with Geoff Emerick, study a

graphic identifying every person on the Sgt. Pepper’s album cover and

read more about the 1967 recording sessions. ________________________________________

It was a shocking declaration.

The world's most successful

pop band had gathered to record a new album. But first, the Beatles

revealed a secret to their producer, George Martin, and sound engineer,

Geoff Emerick.

They had decided to stop touring.

Instead,

they would make music that couldn't be played live. They'd create

something completely new, make sounds no one had heard before.

John Lennon, the band's visionary and mercurial founder, was characteristically blunt.

"We're fed up with making soft music for soft people, " Emerick recalls Lennon saying.

In

the four months that followed, the Beatles and the staff at EMI's Abbey

Road studio created an album that still reverberates through the music

world today.

Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band was

released June 1, 1967 - 40 years ago next month. It helped launch the

Summer of Love and elevate pop to art. The album's searing lyrics, its

pop art cover, even the Day-Glo colors and new mustaches the Beatles

wore, captivated popular culture.

But most important was the music.

Pepper's soaring,

incandescent melodies, psychedelic sound textures and juxtaposition of

rock against baroque, English dance hall and Eastern idioms make up the

root of its power.

There was nothing soft about it.

Emerick,

only 20 at the time, was entrusted to capture those sounds, and in some

cases create them himself. In a wide-ranging interview, he explained

how he did it.

As the Beatles made their auditory ambitions

known in that first meeting, the young engineer suddenly noticed that

everyone was looking at him.

Feeling the weight of expectation from music's biggest clients, he managed only a wan smile.

- - -

From the outside, it seemed the Beatles had peaked.

The

group had recently finished a disastrous tour of the Philippines,

offending Imelda Marcos and getting thrown out of the country. In the

United States, thousands burned their Beatles records, furious that

Lennon had told an interviewer the group was "bigger than Jesus now."

Journalists asked if the Beatles had broken up.

But the Beatles

themselves felt invigorated. Now they could make any kind of music they

wanted, without worrying about reproducing it for ravenous fans.

They began with two songs about the group's Liverpool past, Lennon's Strawberry Fields Forever and Paul McCartney's Penny Lane.

Together with McCartney's vaudevillian When I'm 64, the two songs suggested the new album's theme: a sentimental look back.

But

the concept was whisked away by the record company, desperate for a

single from its biggest act. In those days, EMI kept singles and albums

separate; thus, neither Strawberry Fields Forever nor Penny Lane would make the album.

Such

was the Beatles' creative metabolism at the time that EMI's decision

barely registered. Instead of moping, they began working on the song

that many consider their masterpiece.

- - -

Lennon's new

composition was inspired by a couple of newspaper stories and his

experience acting in an antiwar film. Emerick said the brilliance of A Day in the Life was clear from the first take.

"Shivers just ran down our backs, " Emerick said. "It was just unbelievable."

The

song wasn't finished, but the group began recording anyway. They left a

24-bar section essentially blank, to be filled in later. Beatles roadie

Mal Evans counted the bars and set an alarm clock that went off just as

the gap was finished.

Emerick found he could not scrub the alarm

from the tape; it was locked in with other instruments. But in a happy

coincidence, the song snippet McCartney offered to be placed among

Lennon's verses began: "Woke up, fell out of bed . . ."

There

was still the matter of filling the 24-bar gap. McCartney came up with

the idea: a full orchestra would play a climactic rush of sound.

But

classical musicians aren't accustomed to improvisation. The 40-member

orchestra sitting in Abbey Road's cavernous Studio One looked

dumbfounded.

"The score basically was, well, two notes. Over

24 bars you go from this note to that note, " Emerick said. "It took

about a half hour for that to be explained to them."

The

orchestra, wearing clown noses, party hats, funny glasses and other

fanciful props Lennon wanted the session to be "a happening," played

their parts several times, with Emerick and the studio crew recording

each pass.

The result was breathtaking. Yet the passage still

needed an ending, a resolution to that dramatic buildup. McCartney's

first idea was for the group to hum the final E chord, which they

attempted after the orchestra left. After that proved unsatisfactory,

three of the Beatles and their roadie took to the studio's pianos to

play the final chord.

Emerick wanted that chord to sustain as

long as possible, so he kept turning up the volume as the notes

decayed. Near the end, careful listeners can hear a small squeak. It

was drummer Ringo Starr, moving slightly as he shared McCartney's piano

bench.

"I think Paul sort of gave him a glare, " Emerick said.

Emerick quickly mixed the tracks and played it for the spellbound studio crew.

"It

was basically for the first time going from black and white up till

that point to watching a color film, " he said. "It was like no one had

ever, ever heard anything like it in their lives, you know?"

- - -

The

album still had no unifying theme. McCartney proposed one by giving the

Beatles alter egos. He created an imaginary band that, in his mind,

further freed them from their fans' expectations. Sgt. Pepper was born.

In the title track and especially in the song that followed, With a Little Help From My Friends, Emerick strove to capture McCartney's bass guitar in a new way.

Instead

of pressing a microphone next to the bass amplifier off in a corner of

the studio, as was the norm, Emerick decided to pull the amp into the

middle of the room. He chose a microphone that picks up sound from

front and rear, and he placed it several feet from the amp. Because of

the studio's ambience, the instrument suddenly sounded round and full.

And

because McCartney recorded his bass separately, Emerick was free to

boost its volume in the mix without affecting other instruments.

One of Emerick's enduring memories of the Pepper sessions

is watching McCartney huddled over his Rickenbacker bass, laboring over

every note, long after the rest of the band had left.

"It was always the last thing I would bring into the mix, " Emerick said, "and it was always the loudest thing on the record."

McCartney

didn't limit himself to bass guitar. When lead guitarist George

Harrison couldn't seem to nail his part on the album's title track

despite hours of labor, McCartney picked up his Fender Esquire guitar

and played it in a single take.

- - -

The Beatles' music

was increasingly complex. But Emerick and the Abbey Road staff had to

record it with machines that could hold only four independent tracks of

music at a time.

Some songs on Sgt. Pepper included more than 50 instruments. How did Emerick keep them all in order?

He

did it by "bouncing down" the first four tracks onto a single track of

a second tape machine, freeing up three tracks for new parts. The

technique meant that Emerick had to record each part correctly the

first time - with the appropriate volume, equalization and other

effects. Once they were locked into the preliminary mix, the

instruments couldn't be adjusted individually.

Such a limitation

would cripple modern sound engineers, who often have 50 or more

separate tracks to play with. Emerick believes it actually helped.

"There was nothing superfluous, " he said. "Every overdub meant something; it added something to the track."

But

sometimes it was hard to decide what to overdub. Brilliant and

intuitive, Lennon also was musically inarticulate and struggled to

explain what he was looking for, Emerick said. When it came to his song

Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite, essentially the text of a

Victorian circus poster set to music, the composer told the studio

staff he wanted to "smell the sawdust" in the final recording.

Before Emerick could get him to explain, Lennon left for the night.

Emerick's

solution involved finding some tapes of old steam organ music. He cut

the tapes into pieces, threw them up in the air and reassembled them

randomly.

The resulting swirl of sound was just what the song needed.

"We did what we could for John, " Emerick said. "We tried to smell the sawdust."

- - -

The album sent shock waves across the pop music landscape.

People held Sgt. Pepper parties, putting the record on the player and sitting on the floor, just listening. The Times of London said,

apparently without irony, that the album marked "a decisive moment in

the history of Western civilisation." Beach Boys composer Brian Wilson,

already struggling to top the Beatles' previous album, abandoned his Smile project and sank further into a lethargy of drugs and mental illness from which he took decades to recover.

Thirteen-year-old

American Walter Everett had "no comprehension" of the album's lyrical

content. But its sound "blew me away, " says Everett, now a music

professor at the University of Michigan, who has written two books

analyzing the group's music.

"Nothing stands out like the Beatles and Pepper, for me, " he says.

To

rock producer-engineer Kevin Ryan, who spent a decade researching and

writing a book on the recording methods of the group, Sgt. Pepper "is the sound of a group of guys who just realized, 'Hey, the sky really is the limit!' "

"I think Pepper

was the apex of their career, " he said. "The group finally, completely

shed the mop-tops image and emerged as something else altogether: true

musical visionaries."

As for Emerick, EMI didn't even list his name on the album credits. His groundbreaking work on Pepper won him a Grammy anyway.

After

an accomplished career as an engineer and producer, Emerick last year

wrote a book about his Beatles experiences. Today, 40 years after the Pepper sessions, he remains content with the final product.

"There

were moments on every track . . . that no one had ever heard before, "

he said. "Someone asked me the other day would I ever have changed

anything. No. I would never have changed one thing."

Christopher Ave can be reached at cave@sptimes.com or

(727) 893-8643

(727) 893-8643 .

.

THE BOOK

Here, There and Everywhere

My Life Recording the Music of the Beatles, by Geoff Emerick and Howard Massey, Gotham, $15.

Last modified May 18, 2007, 17:03:50

| Группа "Гости" | RSS

| Группа "Гости" | RSS

| Группа "Гости" | RSS

| Группа "Гости" | RSS