September 5, 2009

Bob Stanley

Who is the fabbest Beatle of them all?

This is a serious message,” it begins. “Peace and love,” it says, at least

once too often. Ringo Starr’s weird trashing of his loveable mop-top

reputation, first on his website and then all over YouTube last year, makes

for painful and hilarious viewing. To give him credit, the man has attempted

to sign everything he’s been sent by fans since 1963; he’s now almost 70 and

wanted to tell the world he can’t keep up. Of course, it might help if he

didn’t say all future fan mail “will be tossed”, or deliver this minor news

item with the scary line, “I’m warning you with peace and love”.

Starr probably wouldn’t have been the people’s candidate for favourite Beatle

before this outburst, not because of any other ill-advised YouTube postings,

or for any animosity towards Thomas the Tank Engine, but simply because he

was the fourth member of a group that featured three of the most talented

singer- songwriters of his generation.

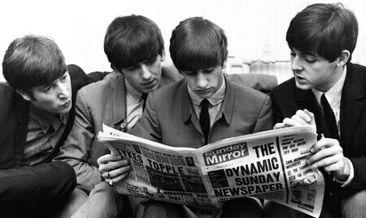

In spite of their oneness, and the inability of anyone outside Britain to tell

them apart in 1964, everyone tends to have a favourite Beatle. At various

points in their career and afterlife the world seems to have had a

collective favourite. In the Eighties, after his death, it was undoubtedly

John Lennon. When Oasis and the Anthology series brought their music back to

the Britpop table in the Nineties, Lennon was still regarded as the most

innovative, the most significant, the sharpest Beatle.

George Harrison was the underdog, the indie Beatle. It might be something to

do with the recent folk boom, or the general feeling of achievement by

understatement in the most lauded pop (Fleet Foxes, Animal Collective) of

the last couple of years, but a straw poll among friends, colleagues and

musicians places Harrison at the top of the table at the end of the

Noughties.

Of course, favourite Beatle and best Beatle aren’t the same thing. “It’s a

peculiar testament,” says Todd Rundgren, the singer and producer who had a

public spat in the NME with Lennon in the Seventies, and played in Ringo’s

All-Starr Band two decades back. “ ‘Favourite’ used to just mean the cutest,

or the funniest. Now each has his own body of work it’s different.”

Starr could probably have claimed the crown when the Beatles first broke in

the States, a time when they — and Starr especially — were regarded as some

new breed of being: half human, half haircut. “I did several tours with

Ringo and he was terrific to work with,” Rundgren says. “Briefly I worked

with him on a Jerry Lewis Telethon in the late Seventies and he wasn’t at

all like John Lennon on the rampage, he was ... a little more jovial. It was

the first time that I’d had any dialogue with Ringo and he must have

remembered it fondly because he called me up years later. He was always

level-headed and easy to deal with. It was the other crazies in the

All-Starr Band I had to look out for! Half the band were in AA and the other

half needed to be. But Ringo was terrific. He just enjoys playing music.”

Gem Archer, guitarist with the currently stalled Oasis, saw that band’s

minutiaeporing Beatles obsession from the inside for ten years. When they

put their sibling rivalries aside, Oasis spent most of the last tour getting

overexcited about the imminent Beatles remasters. Are they all going to buy

them, even though it will be the same music they have owned for decades? “Of

course! We’re all getting hoodwinked again.”

Specifically, Archer is looking forward to the mono versions, most of which

will be available on CD for the first time. “We’ve been on about the monos

for years. I hope they stand up. We got a great mono copy of The White Album

in Japan on tour that we were listening to. It must be a leak. It sounds

incredible.”

Archer’s own Beatles obsession began when he was fed tapes by his cousin from

the age of 8. “I remember hiding The Beatles at the Hollywood Bowl in the

schoolyard. Punk was happening and people thought they were poofs because

they wore ties and stuff. Some kid came to my door and sold me his sister’s

copy of Imagine for 50p. I was known as the Beatles fan in the village.”

Lennon was his favourite: “Of course. It was a journey with him ... It still

is, man. He’s still there with all of us. He was perfect — the Rickenbacker,

the hair, the boots — but he was imperfect. Completely human. He let his

hair down on all of us.”

The odd thing about Lennon, the most subversive Beatle, is that he is now the

one with an airport named after him, the one who wrote the cosy, fathomless,

unofficial world anthem Imagine, the one who created proto-Live Aid “event

pop” with All You Need is Love, and thus, in 2009, the most revered by the

Establishment. Archer’s wife “is a teacher, and they teach him now: Recent

History, Year 5. It’s because he grew up in the war, and then he preached

peace. And of course there’s no danger of him spoiling it by shooting some

granny now.”

In the days before every Beatles-related event meant blanket media coverage, a

small film such as Birth of the Beatles could sneak out on the BBC almost

unnoticed. Forgotten by many, it can only be found now on pirated DVDs. The

kid with the quiff playing Hamburg-era Harrison was John Altman, who would

define small-screen infamy a few years later when he first appeared in

Albert Square as Nick Cotton. His favourite “was always George. He was a

Pisces, like me, and I thought I looked a bit like him. Similar ears. I

think that’s one of the reasons I got the part in Birth of the Beatles. This

kid used to flick my ears from behind in the playground — you know what kids

are like. My mum said, ‘Don’t worry, Clark Gable had ears like that and he

was a pin-up’. So that made me feel better. I wonder if George got stick for

it at school.”

Altman’s first taste of the Beatles “was Please Please Me, on the radio in the

wintertime. I’d never heard that sound before. It was a bit like the first

time I heard Hendrix — exciting and vibrant. The next stage in my Beatles

habit was getting Please Please Me, the album, for Christmas. I left it on

the Dansette record player, and it warped. I remember desperately trying to

iron it flat on an ironing board with a damp towel on top. A sad end.”

As he grew up with the band, Altman would “listen out for George’s

contributions, the songs on Rubber Soul and Revolver, like Taxman. They were

quite special. And they built up to All Things Must Pass — every musician

has an apex and I think that was his.”

They never met. “Pete Best [the preRingo drummer] was the technical adviser on

Birth of the Beatles, and he was the only Beatle I met. The only quote I

heard from any of them about the film was that Ringo found it quite

amusing.” He still sounds slightly disappointed today.

Harrison’s allure could also be down to his mystique, which allows fans to

fill in the blanks any way they wish. Lennon and McCartney are open books,

foibles exposed, but if Harrison had a dating profile it would be of the one

photo, one-liner variety, enigma unquestionably enhanced. He was the only

Beatle without an obvious role. “Paul was the cute one,” recalls Rundgren,

“John was the smart one; each had a bailiwick they were in charge of. Ringo

was the cuddly one. The short, homely, cuddly one. Girls liked Ringo, at

least girls who thought Paul was out of reach, too cute by half.”

Rundgren’s favourite is also Harrison. “For me, his contribution was to

elevate guitar to a special status. I’m unaware of anyone using the

expression ‘lead guitar’ before the Beatles, and that was a position

highlighted by George Harrison. It drew guitar players into taking their

playing more seriously. Solos on records could’ve been anything — a

saxophone, an ocarina — but on Beatles records I’d always look forward to

how that little interlude would be filled by lead guitar. In the case of

George Harrison it was concise, accessible, a bit clever. It was also short

and accessible enough for most guitarists to work out, even without George’s

finesse.”

In the early Eighties, the Orange Juice singer Edwyn Collins had his “My Top

Ten” list printed in Record Mirror. Alongside entries by Al Green and George

McCrae was the Beatles’ She Said She Said — Collins wrote that he

particularly liked “George’s astringent guitar”. I was a huge Orange Juice

fan — I remember having to look up “astringent”. When Collins met his

partner Grace Maxwell he told her that his “favourite guitarists were John

Fogerty and George Harrison. When people say they don’t like the Beatles,

they may as well say they don’t like fresh air. ‘I hate fresh air!’ It’s

ridiculous.”

After Collins had a stroke in 2005, lying in a hospital bed he didn’t want to

hear any music. Three years before he had written a song called The Beatles,

which managed to lyrically condense their career inside four minutes. “After

nine or ten weeks Grace brought in an old tape that I’d made, a compilation.

The first track, I remember, was Promised Land by Johnnie Allan, and the

second had me in tears.”

“Tears?” Grace says, laughing. “You were in floods! You were bawling.”

The song was Photograph, sung by Starr and written by Harrison.

Mojo magazine has featured some combination of Beatles on its cover more than

a dozen times in just under 200 issues. The editor, Phil Alexander, reckons

that there are still plenty of untold, or at least unexplored, stories to

make them newsworthy. He has noted Harrison’s ascent to the summit. “You can

see why people say ‘George, now — he was the coolest’. Not acerbic like

Lennon, not thumbs aloft, and he wasn’t playing the Ringo good-guy role. He

was mystical and cool. He’s the fashionable choice. Stupid as it might

sound, I think the unsung hero of the Beatles today is Paul.”

If favourite Beatle and best Beatle are not the same thing, it could be true

that Paul McCartney — the most successful songwriter in British pop history

— is undervalued. “It’s just deeply unfashionable to say Paul is your

favourite,” Alexander says. “It sounds callous to wonder how people would

feel if he died tomorrow because it might just happen, and I don’t mean to

use death as a barometer, but it’s true — I think they’d say he was the best

Beatle. After John Lennon died, Paul said that his exterior had been a

front, and I sometimes wonder how he views his own exterior. The way he

often says, ‘We were a pretty good little group’, that kind of false

modesty, can be irritating, but if he believed everything people said about

him he’d go mental. To have survived what he survived, you have to respect

him.”

As a teenager, Korky Seymour worked in Liverpool’s Beatles Shop, on Mathew

Street. “People would ring up and say ‘Can I speak to the Beatles?’ We got a

bundle of letters for them every day. Not everyone was a loony, some were

just asking for mugs, or fridge magnets, or where Paul lived, but quite a

few would say ‘I LOVE YOU’ in scrawly capital letters. Paul got the most,

definitely. George? No. He was really the outsider, not like today. He was

not as fashionable.”

Seymour met three former Beatles, but McCartney left the greatest impression

on her. “I was 14 and I’d got a Saturday job there. It was just before he

did the Liverpool Oratorio. He was rehearsing at the Philharmonic one week,

and me and my best friend waited outside. His crew were really nice — they

could tell we were just kids, not crazy fans. We went most days, and Paul

would come out and say hello. It must have been Easter because one day he

brought us all Creme Eggs.”

Up in Glasgow, Grace Maxwell had to use her imagination for her Beatle fix.

“You know the metal poles that hold up clothes lines? There were four in our

back garden. We would make each one a Beatle. You’d run over, snog the

clothes pole, and say which Beatle it was. Mine was Paul. Does that sound

weird?”

“Paul is the best Beatle,” reckons Seymour. “It’s obvious. Take Double Fantasy

and McCartney II, made in the same year (1980). I heard Front Parlour (from

McCartney II) in a club in Shoreditch a few years ago, and everybody was

asking what it was, everyone thought it was some German electronic group.

Paul was thinking of the future, how the Eighties would be. On Double

Fantasy, John was going back to his roots, again. Boring, really. Paul still

makes a real effort, and maybe that’s just not fashionable.”

Phil Alexander is inclined to agree. “John’s crusading mentality made him a

cult figure, compounded by his passing. He was the bravest — the records he

made with Yoko are still controversial, so ahead of their time, but Paul

still wants to do new things even to this day. The last Fireman record was

really musical and brave, despite the bizarre, politician aura around him.

Rundgren, possibly keen to start another spat with a Beatle in the British

press, feels a little differently. “George peaked around the Bangladesh

concert. Ringo did Photograph, that was a good song. John’s career was

healthy because of album-oriented radio, he wasn’t played so much on AM. But

Paul was getting regular Top 40 attention, even if it was a crappy piece of

junk like Silly Love Songs. He’s so erratic. He pulled it off with Band on

the Run. But the stuff with Michael Jackson — Say Say Say and The Girl is

Mine? Dreck! It’s weird. He’s too willing to do anything. When he thinks

he’s not on AM radio enough he makes an attempt to do it and it comes out

embarrassing, back to his baby talk again. He doesn’t realise how much

things have changed.”

A compilation of tracks from the last five McCartney studio albums would, I

reckon, be enough to cement his legend. They contain songs that are at least

equal to any of his post-Beatles output, and good enough for the

thumbs-aloft, “good little band” persona to be forgotten: The End of the

End, from Memory Almost Full, is quite possibly the saddest, and most

elegant, song written by any sexagenarian pop star.

The Beatles’ reach goes beyond just their music. “If anybody was going to make

the Sixties explode it was John Lennon,” says Archer. “It wasn’t David

Crosby. It certainly wasn’t Elvis. And Dylan didn’t put himself up for it,

did he?”

And Starr? His comments about Liverpool on the Jonathan Ross show have to be

seen as tongue in cheek, his fan-mail comment the outburst of a grouchy

69-year-old having a bad day. Seymour, who has had to field only a fraction

of the questions from Beatles nuts that the overworked Starr has, nails the

conundrum.

“My favourite Beatle is the Beatles. They are like four quarters that make up

a circle. They’re inseparable.”

| Группа "Гости" | RSS

| Группа "Гости" | RSS

| Группа "Гости" | RSS

| Группа "Гости" | RSS