Something in the way she wrote.May 5, 2007

When a young Beatles fan wrote to George Harrison in

1963, she scarcely expected a reply. But a letter did come back -

from his mother. It was the start of an extraordinary

correspondence, writes Lilie Ferrari.

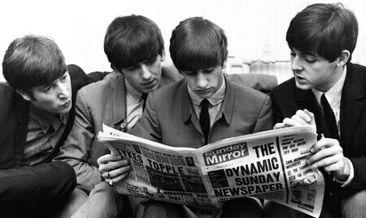

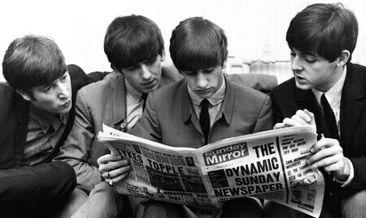

IN 1963, I WAS 14 AND, LIKE almost every girl in Britain, I fell

in love with a Beatle. "My" Beatle was George Harrison. From the

first photograph I saw of the Fab Four, I was drawn to his dark

eyes, serious face and enigmatic demeanour. He rarely smiled, even

when he was being funny, and this made him all the more mysterious

and enticing. Compared to the uncouth boys I had to deal with at

school every day, George was a delicate, idealised vision of what I

thought boys ought to be like. If he had pimples, I never saw them.

If he swore, I never heard it. I never saw his hair greasy, his

armpits damp, his shoes scuffed.

In short, he was perfect.

We had just moved to Norwich, eastern England, and I had missed

a Beatles concert by a few weeks; but a girl in my class had

somehow obtained all the Beatles' home addresses (I daren't think

how, looking back) and was selling them at playtime for half a

crown each. A bargain, I thought, handing over my cash eagerly.

Immediately upon the exchange, 174 Mackets Lane, Liverpool, became

the repository of all my fantasies.

That day I hurried home to compose my first letter to George. I

had discovered the joy of words, and wasn't about to be intimidated

into single syllables by writing to a Beatle. I don't remember

exactly what I wrote, but in spite of my best intentions I suspect

it was a gauche jumble of repressed adoration, along the lines of

"You're the best Beatle" and "I much prefer From Me to You

to Come On by the Stones". I don't remember waiting for

the postman every morning. By then the Beatles had started their

journey into the stratosphere (it was the year the term Beatlemania

was coined) and I guess I assumed I was too small a cog in the

great Beatle wheel to merit any kind of response.

But one day a letter with a Liverpool postmark did come,

addressed to me in careful looped handwriting. I opened it with

trembling fingers and, instead of a letter from George, found one

from his mum, Louise.

After a few niceties and general bulletins about the boys'

progress, a question leaped off the page: "Are you," she asked, "by

any chance related to a writer called Ivy Ferrari, who writes

doctor-and-nurse romances?"

I bellowed a great scream that brought the family running: my

mother was Ivy Ferrari, a romantic novelist churning out Mills

& Boon paperbacks with titles like Nurse at Ryminster,

Doctor at Ryminster, Almoner at Ryminster. I couldn't believe

it - I might be a fan of her son, but Mrs Harrison was evidently a

fan of my mother. I felt as if I had been raised from one among

millions to a special place in Mrs Harrison's head.

Of course I wrote back to tell her that I was indeed Ivy

Ferrari's daughter. I was happy to have made the connection - but

so, it seemed, was she. I couldn't quite grasp it. Beatles were

glamorous; my mum was a harassed woman with inky fingers, unruly

hair and scruffy skirts who sweated over a typewriter all day. How

could they compare?

In the past I might have been indifferent to the overwrought

love lives of the fictional staff of Ryminster hospital, but now

they seemed to take on a glamour of their own. George never wrote

to me, and my mother never wrote to Mrs Harrison, but the two of us

began a correspondence that lasted for several years - years that

took her from the Mackets Lane council house to a smart bungalow in

Appleton, George from gangling teenage guitarist to married man,

and me from schoolgirl to young woman.

I sent Mrs Harrison signed copies of my mother's novels. She

sent me signed pictures of the Beatles. I asked her intense

questions ("Which one is your favourite, besides George?" Answer:

"John, because he does the tango with me in the kitchen and makes

me laugh"). She interrogated me about the mysteries of my mother's

creations, such as whether my mum knew any real doctors like Dr

David Callender. ("He was fairly tall and tough-looking, with

tawny-brown hair and a lean, intent face. His eyes were dark and

compelling, so full of fire and life they drew me like a magnet . .

.")

On my 15th birthday, Mrs Harrison sent me a small piece of blue

fabric, part of a suit George had worn at the Star Club in Hamburg.

Once, I got a crumpled newspaper cutting containing a photo of the

Beatles with their scribbled signatures on it, and a big lipstick

kiss, which, she said, had been planted there by John Lennon.

She sent me notes that George wrote her on used envelopes: "Dear

Mum, get me up at 3, love George". She wrote on the backs of old

Christmas cards and odd bits of paper - I never knew why. She told

me funny stories about her upbringing in Liverpool, a world of men

in caps on bikes and old ladies with jugs of gin.

I told her about my life in Norfolk, about my sisters, my pony,

the dog, my mother. I told her things I didn't tell anyone else -

my fear of failure, my terrible, hidden shyness, my longing to have

real adventures, lead a different kind of life to the quiet, rural

existence I endured. She was my invisible friend, the silent

recipient of everything I had to say.

She always answered my questions, and offered up teasing

glimpses of life as the mother of a superstar - "I'm sitting by the

pool with Pattie. Had a lovely time at the film premiere" - remarks

tantalisingly combined with more mundane observations about

knitting and cakes. Of course I never mentioned "real" boys who had

caught my eye - that would have been somehow unfaithful to George.

That was the only omission I can remember - apart from never

articulating how I felt about her son, because I wanted her to

think of me as a "normal" girl, and not the wide-eyed obsessive I

really was.

After several years the gaps between our exchanges grew longer,

as real life began to get in the way of teenage fantasies. I can't

remember which of us wrote the last letter, but by the time I was

18 and working in London, the correspondence had petered out.

Soon after we had slipped from each other's lives, I found

myself standing a few feet away from George himself, in the Apple

boutique on London's Baker Street. He looked tired and

unapproachable.

The George that I had conjured up in the kitchen of Mackets

Lane, propping notes for his mum on the mantelpiece, seemed a

kinder, gentler prospect than the gaunt-looking superstar standing

before me who might just tell me to get lost. He was close enough

to speak to, but I've never been sorry that I backed away in

silence.

Mrs Harrison died in 1970 when I was 21. I remember reading

about it in the papers. I grieved for her on my own, and remembered

her small acts of kindness to a girl in Norfolk she had never met.

Her son, of course, made an enormous mark on my life without ever

knowing it. I even married someone who embodied all the things I

thought George represented: quiet strength, spirituality, the same

dry humour, the dark good looks.

My husband Colin had been, among other things, a roadie and the

owner of punk record shops. Fortunately, he also had a sense of

humour and a high level of tolerance. He learned to live with the

omnipresence of George, and would sign cards to me "Love from

George and The Other One".

As the years passed, my life came into focus and George receded.

He married, had a son, as did I. I went back to live in a Norfolk

cottage, while George retired to a Gothic mansion in Henley. In

1994 I went to Liverpool for the first time with Colin, as a

football supporter rather than a Beatles pilgrim: Norwich City were

playing at Anfield.

I took time out to stand in front of 174 Mackets Lane and tried

to imagine Mrs Harrison sitting at the window in the front room,

answering my letters. I wanted to weep, but I didn't. When Norwich

scored the winning goal that afternoon and we leapt to our feet, I

cheered instead for that kindly Liverpudlian who took the time and

trouble to light up my teenage years.

I've gradually lost the priceless relics of those years. They

would have made me rich if I hadn't been so careless with my

belongings; then again, I would never have sold them. So my side of

that eccentric correspondence has all but disappeared, along with

my youth.

In September 2001, Colin died of Hodgkin's disease. A month

later, George was dead, too. It felt as if two distinct parts of my

life had ended all at once: my dreamlike girlhood, and my real,

adult life with a beloved partner and friend.

But every day in my study at home, I look at something that

binds these two parts together. It's a photograph of George taken

in 1962 in Hamburg by Astrid Kirchherr (girlfriend of "fifth"

Beatle Stuart Sutcliffe).

Colin secretly sought it out, hand-made a frame for it, and gave

it to me on my 40th birthday. It is one of my most treasured

possessions.

GUARDIAN

| Группа "Гости" | RSS

| Группа "Гости" | RSS

| Группа "Гости" | RSS

| Группа "Гости" | RSS